Amid all the carnage, in emerging markets and developed ones, it is nice to discover some good news. At least it is if it can genuinely be believed. Figures out on Monday suggested Africa’s headline sales managers’ index, broadly analogous to the purchasing managers’ indices widely followed elsewhere, rose to a 28-month high in August. The index ticked up to 60.2, from 59.3 in July, on a scale where 50 is the dividing line between an increase or a decrease in activity, the highest rate since May 2013 (see the first chart).

The service sector led the way, with an SMI of 61.1, but manufacturing was not far behind, at 58.1. All of the five sub-components that feed into the headline figure were also positive, notably the business confidence index, which measures how sales managers expect the economy to perform over the coming months, which came in at a punchy 75.6.

Wonderful news, of course. But then we also know that Africa is far from immune to the economic and financial chaos sweeping the planet. China’s imports from Africa have slumped more than 40 per cent from their peak, in value terms at least, as the prices of oil and other commodities have collapsed (see the second chart). That Africa’s imports from China have also started to fall suggests this weakness has fed through to consumer spending.

Many African economies are running down their foreign exchange reserves as they battle to stem, or at least slow, the falls in their currencies. This pressure is also forcing central banks to maintain tighter monetary policy than their domestic situations would merit.

Admittedly, the IMF hailed the “resilience” of sub-Saharan Africa when it produced its latest World Economic Outlook document in April. But even at that point, before the current rout really kicked in, the IMF foresaw economic growth slowing to 4.5 per cent this year, from 5 per cent in 2014. For major north African countries, such as Egypt and Algeria, projected growth was weaker still, at 4 per cent and 2.6 per cent respectively.

So how much store, if any, should one put on the SMI index? It would appear to have a decent pedigree, being produced by World Economics, whose parent company Information Sciences developed the European and Asian PMI indices, now owned by Markit.

However, the breadth of its African product is rather limited, based on activity in just four countries: South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt and Algeria, although this quartet does provide a reasonably broad mix.

Of these four countries, Nigeria currently has the highest SMI reading, 66.3, followed by Egypt (64.2), Algeria (58.9) and South Africa (53.6). Perhaps more tellingly, the index appears to be more than a little obscure. Even Jan Dehn, head of research at Ashmore Investment Management and an old African hand, says he has not heard of it.

Is its upbeat message credible? Here opinion differs. Joseph Rohm, an African equity portfolio manager at Investec Asset Management, suggests possibly so. “That it reflects the manufacturing and service sectors, it is to some degree plausible,” says Mr Rohm, who argues these arenas have remained robust, even as commodity exports have tumbled.

He points to Nigeria, an oil exporter that has enjoyed strong growth over the past decade. Even there, Mr Rohm says, “the growth has come in the manufacturing and service sectors,” with the oil industry pretty much “stagnating” over the past decade.

In countries such as Nigeria and Kenya that have rebased their gross domestic product calculations, it was service industries such as telecoms and media, as well as manufacturing that were found to be larger than expected. “In a world where emerging market growth is falling and commodity prices are under pressure, I believe there are some really healthy underpinnings. The cost of labour has become cheaper and cheaper relative to China, for example, [so] low-skilled assembly plants are being constructed,” says Mr Rohm, who points to investment by Chinese shoemakers in Ethiopia and Asian multinationals such as Honda, LG and Nissan in Nigeria.

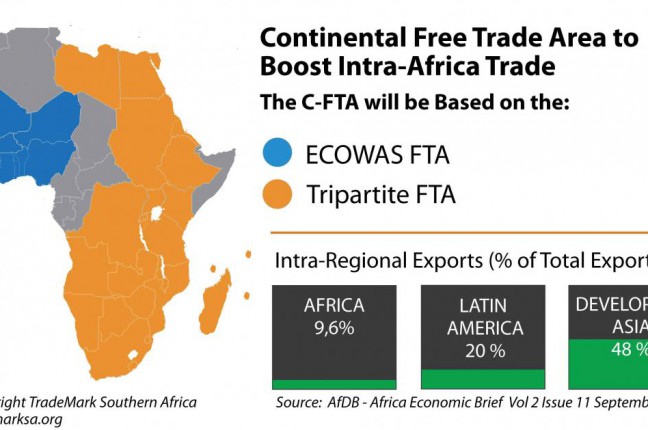

“I don’t think what we are seeing in the emerging market world has really affected that to any degree,” he adds, pointing instead to beneficiaries from the wider market crash, such as the countries and companies in east Africa that are gaining from low oil prices. Moreover, despite data such as that above showing the slump in Africa’s trade with China, Mr Rohm believes intra-African trade is rising, albeit from a low base, amid efforts to remove barriers to such activity.

“Intra-African trade today is 5 per cent of GDP, in Europe it is 40 per cent,” he says. “In South Africa trade north of the border was insignificant going back 10 years. Now every single corporate has a strategy to increase its trade north of the border.”

Others are not convinced, however. “Our view is that growth in Africa is slowing pretty sharply,” says William Jackson, senior emerging market economist at Capital Economics. “I find it pretty surprising that some of the survey-based data is pointing to some improvement.”

Mr Jackson accepts that the export-led commodity sectors are bearing the brunt of the pain, but says in turn that this is eroding many governments’ foreign currency earnings, putting pressure on them to cut public spending.

He predicts that South African GDP data, due on Tuesday, will show growth has slowed to just 0.4 per cent annualised, quarter on quarter, while Nigerian data, which may also come on Tuesday, will show year-on-year growth falling from 3.9 to 3.5 per cent.

As for Egypt and Algeria, he believes the former’s economy has slowed due to restrictions on access to foreign currency that have hit manufacturers, while the latter has been damaged by its reliance on oil and gas exports.

Mr Dehn also points to the “major macroeconomic adjustments” being faced by exporters of oil and other hard commodities, leading him to expect a slowdown. But he does believe some countries, such as exporters of food and other agricultural produce, are less affected.

Yet he does hold out hope that the sell-off, in bond markets at least, may be overdone. “Lowly rated African bonds are the first to be cut by market makers due to regulatory rules. Hence, liquidity, and therefore prices, falls more rapidly than justified by fundamentals,” Mr Dehn says.

South Africa's government will impose a 10 percent import tariff on steel imports to protect the struggling industry, with the possibility of hiking them further, an industry body said on Monday. Cheap imports from China are hurting steel makers in South Africa, which currently does not have import duties on steel. As many as 200,000 jobs are at risk due to a global supply glut of the commodity, ArcelorMittal South Africa has warned.

South Africa's government will impose a 10 percent import tariff on steel imports to protect the struggling industry, with the possibility of hiking them further, an industry body said on Monday. Cheap imports from China are hurting steel makers in South Africa, which currently does not have import duties on steel. As many as 200,000 jobs are at risk due to a global supply glut of the commodity, ArcelorMittal South Africa has warned. South African Logistics Company Imperial Holdings reported flat full-year profits on Tuesday as its vehicle import and distribution division suffered from feeble demand and a weakening currency in its home market.

South African Logistics Company Imperial Holdings reported flat full-year profits on Tuesday as its vehicle import and distribution division suffered from feeble demand and a weakening currency in its home market. The official statements are clear: Regional leaders and policymakers want to make the 26-member Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) the main stepping stone towards the gradual establishment of the Continental FTA (CFTA) comprising the 54 members of the African Union. Indeed, during the June 2015 African Union Summit in Johannesburg leaders ambitiously insisted that the negotiations on goods and services for the establishment of the CFTA be concluded by 2017. High-level political will seems to be strong. The challenge, now, is to convert this political will into something more than a paper agreement.

The official statements are clear: Regional leaders and policymakers want to make the 26-member Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) the main stepping stone towards the gradual establishment of the Continental FTA (CFTA) comprising the 54 members of the African Union. Indeed, during the June 2015 African Union Summit in Johannesburg leaders ambitiously insisted that the negotiations on goods and services for the establishment of the CFTA be concluded by 2017. High-level political will seems to be strong. The challenge, now, is to convert this political will into something more than a paper agreement. Amid all the carnage, in emerging markets and developed ones, it is nice to discover some good news. At least it is if it can genuinely be believed. Figures out on Monday suggested Africa’s headline sales managers’ index, broadly analogous to the purchasing managers’ indices widely followed elsewhere, rose to a 28-month high in August. The index ticked up to 60.2, from 59.3 in July, on a scale where 50 is the dividing line between an increase or a decrease in activity, the highest rate since May 2013 (see the first chart).

Amid all the carnage, in emerging markets and developed ones, it is nice to discover some good news. At least it is if it can genuinely be believed. Figures out on Monday suggested Africa’s headline sales managers’ index, broadly analogous to the purchasing managers’ indices widely followed elsewhere, rose to a 28-month high in August. The index ticked up to 60.2, from 59.3 in July, on a scale where 50 is the dividing line between an increase or a decrease in activity, the highest rate since May 2013 (see the first chart). It is no secret that Bharti Airtel’s African adventure has not quite gone to plan. But the Indian-based company and the world’s third largest mobile carrier may have found an ace up its sleeve to help spur the company’s business on the continent: Partnering with Facebook.

It is no secret that Bharti Airtel’s African adventure has not quite gone to plan. But the Indian-based company and the world’s third largest mobile carrier may have found an ace up its sleeve to help spur the company’s business on the continent: Partnering with Facebook. Concerns of a slowdown in China, the world’s second largest economy and Africa’s top trade partner, after the Asian giant devalued its currency by 2 percent a fortnight ago has seen markets across the world retreat to multi-year lows.In Africa, where most economies rely heavily on sale of commodities, currencies have been hit or are expected to be hurt by the slowdown in China’s growth, a major buyer of raw material from sub-Saharan Africa.

Concerns of a slowdown in China, the world’s second largest economy and Africa’s top trade partner, after the Asian giant devalued its currency by 2 percent a fortnight ago has seen markets across the world retreat to multi-year lows.In Africa, where most economies rely heavily on sale of commodities, currencies have been hit or are expected to be hurt by the slowdown in China’s growth, a major buyer of raw material from sub-Saharan Africa. President Jacob Zuma arrived in Gaborone, Botswana on Sunday ahead of the 35th Ordinary Southern African Development Community (SADC) heads of state summit, the presidency said.

President Jacob Zuma arrived in Gaborone, Botswana on Sunday ahead of the 35th Ordinary Southern African Development Community (SADC) heads of state summit, the presidency said. President Jacob Zuma arrived in Gaborone, Botswana on Sunday ahead of the 35th Ordinary Southern African Development Community (SADC) heads of state summit, the presidency said.The summit runs from Sunday to Tuesday, under the theme of accelerating industrialisation of the bloc's economies, through transformation of natural endowment and improved human capital, spokesperson Bongani Majola said in a statement.

President Jacob Zuma arrived in Gaborone, Botswana on Sunday ahead of the 35th Ordinary Southern African Development Community (SADC) heads of state summit, the presidency said.The summit runs from Sunday to Tuesday, under the theme of accelerating industrialisation of the bloc's economies, through transformation of natural endowment and improved human capital, spokesperson Bongani Majola said in a statement. Chalk up a major win for global health: according to the World Health Organization, Africa has been free of wild cases of Polio since July. This comes down to a dedicated vaccination campaign that has advanced the continent towards zero cases.This news doesn’t mean that the continent is completely free if the disease. Africa is still a little ways from zero cases: WHO reports that there’s still some ongoing work in Somalia, Kenya and Ethiopia, but that in each case, the transmission of the illness has been interrupted. On August 11th, 2014, Somalia reported its last case, and in July, according to the WHO, the final country to report zero cases was Nigeria.

Chalk up a major win for global health: according to the World Health Organization, Africa has been free of wild cases of Polio since July. This comes down to a dedicated vaccination campaign that has advanced the continent towards zero cases.This news doesn’t mean that the continent is completely free if the disease. Africa is still a little ways from zero cases: WHO reports that there’s still some ongoing work in Somalia, Kenya and Ethiopia, but that in each case, the transmission of the illness has been interrupted. On August 11th, 2014, Somalia reported its last case, and in July, according to the WHO, the final country to report zero cases was Nigeria. She is black and trendy, and young South African girls are learning to love her. Meet Momppy Mpoppy, who is a step ahead of other black dolls across Africa who are often dressed in traditional ethnic clothes. Decked out in the latest fashions and sporting an impressive afro, complete with a tiara, Momppy could play her own small part in changing the way that black children look at themselves.

She is black and trendy, and young South African girls are learning to love her. Meet Momppy Mpoppy, who is a step ahead of other black dolls across Africa who are often dressed in traditional ethnic clothes. Decked out in the latest fashions and sporting an impressive afro, complete with a tiara, Momppy could play her own small part in changing the way that black children look at themselves. Despite our drought restrictions in Central Texas, water is still not that hard to come by. In other parts of the world however, it’s a much different situation.But local organization Well Aware is trying to change that. Well Aware is an Austin-based nonprofit that funds and implements clean water systems for impoverished communities in Africa.

Despite our drought restrictions in Central Texas, water is still not that hard to come by. In other parts of the world however, it’s a much different situation.But local organization Well Aware is trying to change that. Well Aware is an Austin-based nonprofit that funds and implements clean water systems for impoverished communities in Africa. Gary Robinson is flushed with success. In his recent business trip to Nairobi, he oversaw his company’s first foray into bridging the markets of China and Africa, using the UAE as its base.

Gary Robinson is flushed with success. In his recent business trip to Nairobi, he oversaw his company’s first foray into bridging the markets of China and Africa, using the UAE as its base. A new master’s degree that will be offered by 12 universities across Africa aims to develop the continent’s next generation of public policy leaders.The master’s in research and public policy will give aspiring and practising development professionals an understanding of the common challenges confronting countries across the continent, such as education, poverty and HIV/Aids, while training them in global social policy concepts.

A new master’s degree that will be offered by 12 universities across Africa aims to develop the continent’s next generation of public policy leaders.The master’s in research and public policy will give aspiring and practising development professionals an understanding of the common challenges confronting countries across the continent, such as education, poverty and HIV/Aids, while training them in global social policy concepts. Airbnb, the world's leading service to rent out rooms or properties over the Internet, has announced plans to rapidly accelerate its growth in Africa, particularly in key markets such as Kenya and South Africa.

Airbnb, the world's leading service to rent out rooms or properties over the Internet, has announced plans to rapidly accelerate its growth in Africa, particularly in key markets such as Kenya and South Africa. Africa has made great strides towards eradicating polio but the job remains to be finished through strengthened immunization campaigns and surveillance measures, according to the United Nations.

Africa has made great strides towards eradicating polio but the job remains to be finished through strengthened immunization campaigns and surveillance measures, according to the United Nations. Public Diplomacy and Regional Infrastructure Initiative News. A new Somalia is emerging,” believes Ahmed Tall, a business and accountancy lecturer at Mogadishu’s SIMAD University.

Public Diplomacy and Regional Infrastructure Initiative News. A new Somalia is emerging,” believes Ahmed Tall, a business and accountancy lecturer at Mogadishu’s SIMAD University.